In the 21 months since I posted ”Why I Prefer Using a Pencil” on 2H Pencil, technology has marched on. We’ve been through slightly more than one cycle of the phenomenon described by Moore’s Law, that integrated circuits double in performance every 18 months. Devices have gotten smarter and smaller and more connected. BIM, 3-D modeling, 3-D printing and the Cloud are the current darlings of architectural office technology.

In this time period, I’ve continued to think about my relationship to technology. Rather than classify myself as a “tech geek” or a “non-tech geek”, I am, simply, VERY selective about the technology I adopt and use regularly. I prefer a car with a stick shift, because I like to feel the workings of the engine. I prefer not to have a phone on my person at all times, because it feels intrusive and distracting. I prefer to have GPS available when I am on the road. I still prefer using a pencil when it comes to drafting.

For a while in my career, I was in sync with my professional peers with regard to architectural office technology. And when offices began to replace manual drafting with CAD, I learned the fundamentals along with everyone else. But by then, I was more involved in the management than the production side of projects; at that time, CAD was used strictly for production of construction documents. So I used a red pencil on printouts more than I sat at the Microstation.

I was not in the habit of using CAD when I started my own firm twenty years ago. Laura Kraft • Architect is intentionally a one-person firm, structured so that can follow my preferences as I see fit. As a solo practitioner, I have no need for in-house team coordination/collaboration/sharing. Processes and findings are all stored in my head or on paper, or as digital files in Word, Excel, WordPress or ArchiOffice. In addition to these technologies I do use, I’ve got an iPad on which the mail, web and portfolio apps are the most useful for my architecture practice. However, I find that in the course of a day, I still prefer a notebook to a note-recording app.

I’ve got Vectorworks and Sketchup on my office computer, and can get around both programs. I use them on rare occasions when they can do something that the combination of a pencil, an enlarging & reducing copier, a scanner, a digital camera, and/or a quick chipboard model can’t do.

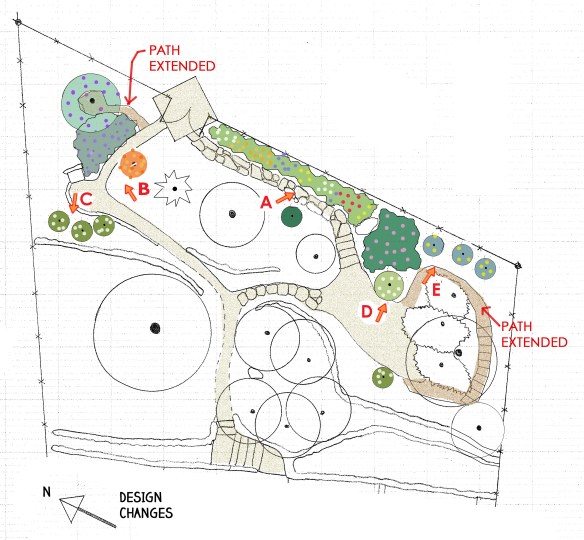

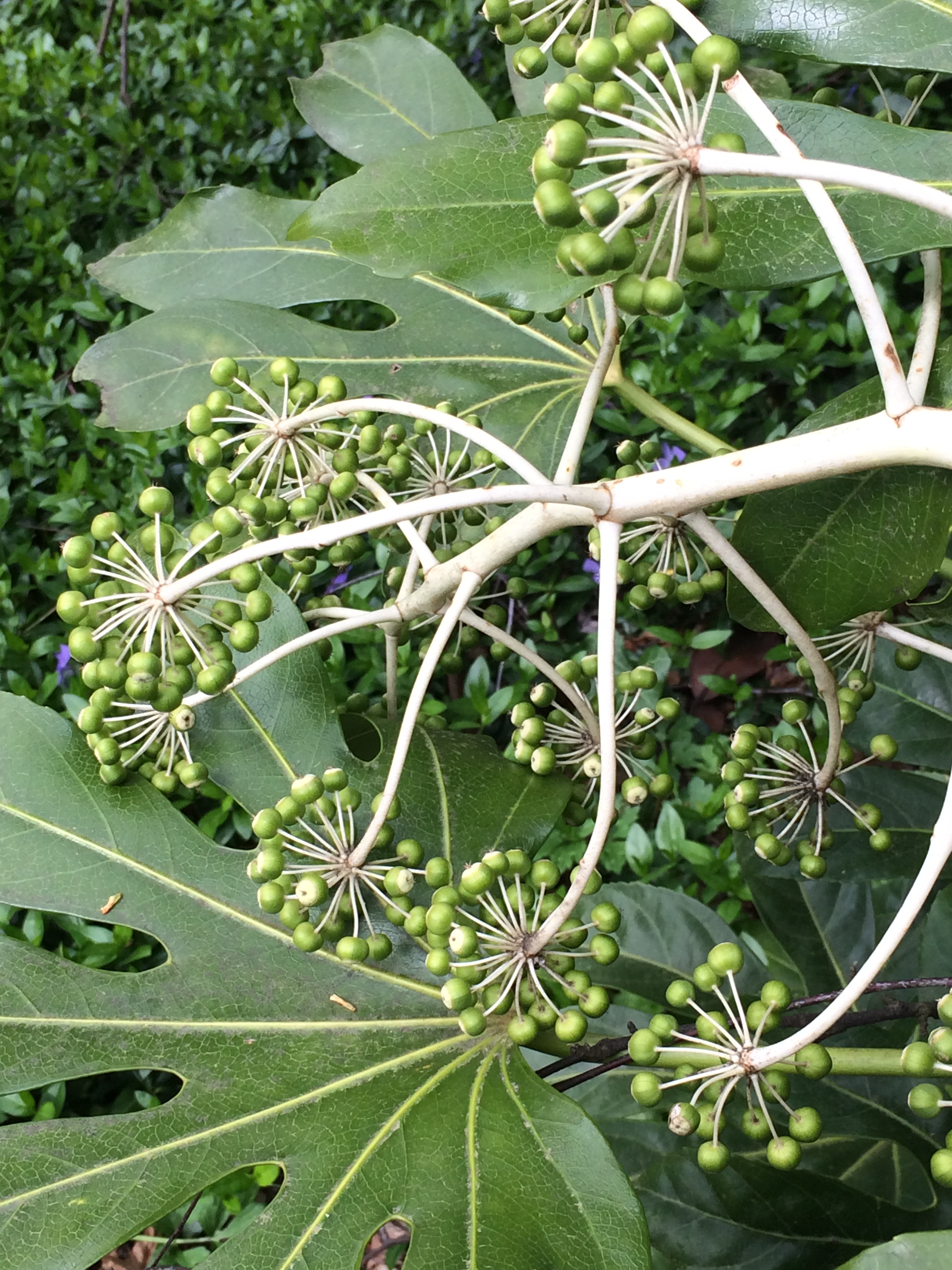

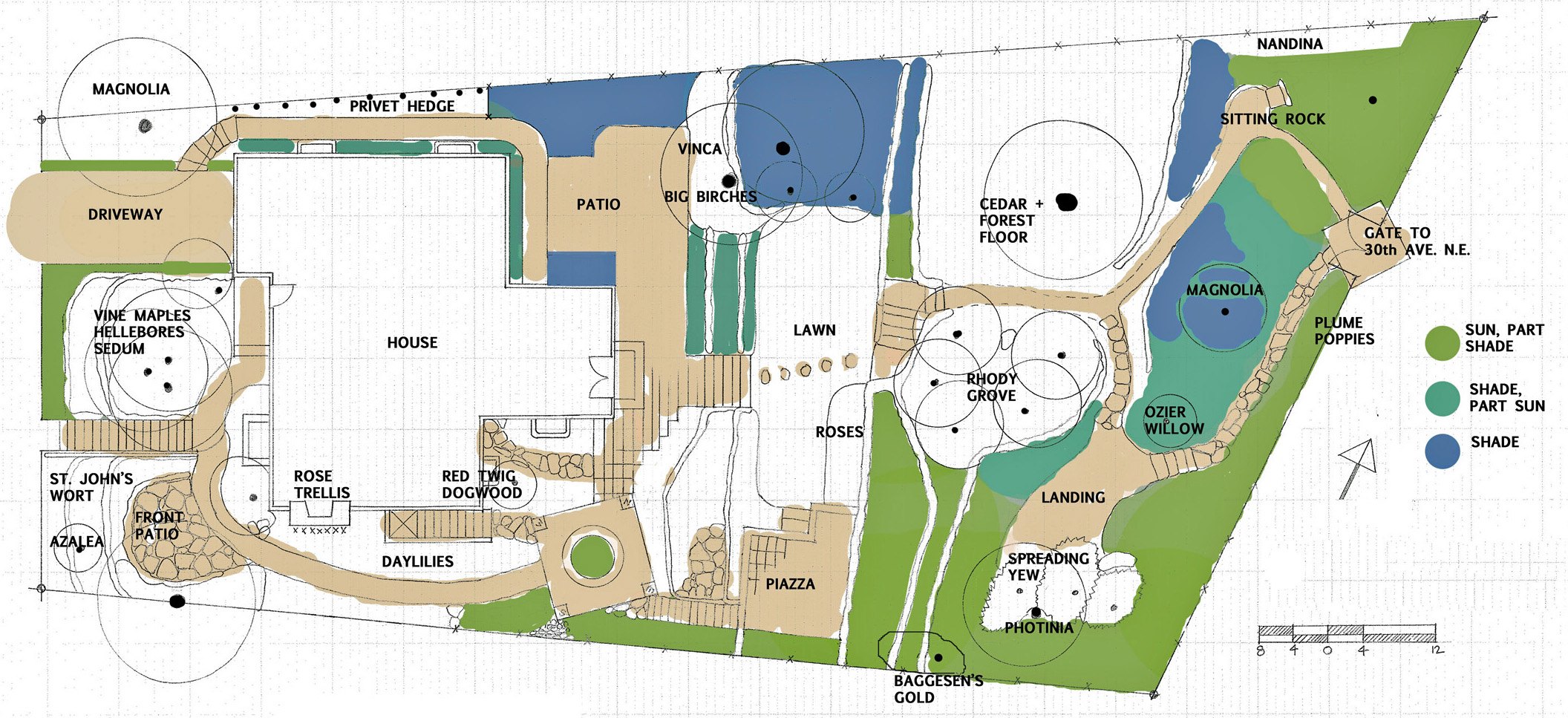

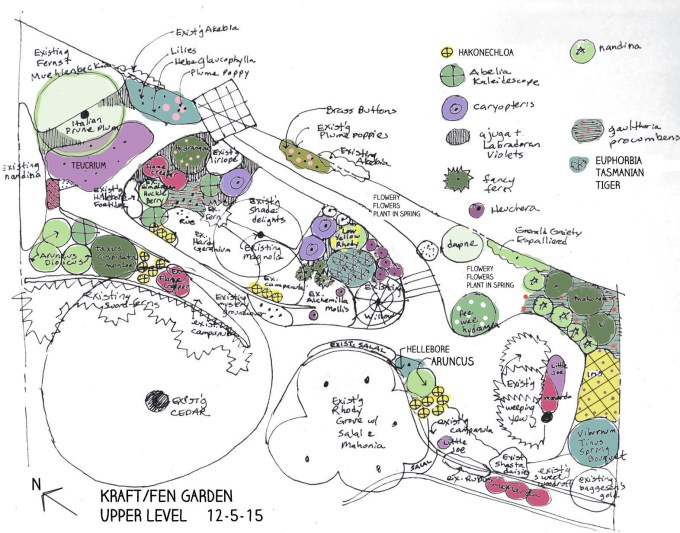

As mentioned in my first post, for the scale and one-off character of custom residential design, the focus of my practice, I believe manual drawing is a viable and appropriate tool. Hand drawn/drafted Pre-design and Schematic drawings are perfectly expressive, informative, loose and evocative for clients’ needs. Custom residential construction documents do not necessarily require the extreme precision available and inherent in CAD.

For me, some significant points against CAD are these: in my office, there is no IT department except for a portion of my own left-brain. When glitches occur, as they do according to Murphy’s Law, it’s incumbent on me to figure them out and fix them. Problems are eventually solved, but at often at too high a cost of time and aggravation. Add to this the necessary, frequent, and expensive upgrades to keep the system viable. Sometimes, advanced technology can take more than it gives.

However, when an un-filled need arises, I can enthusiastically embrace a high-tech approach, if it holds a workable solution. As an example, in the past 7-8 months, I have given free rein to a strong artistic impulse, which has expressed itself as digital art, created with Photoshop Elements, and then printed on a high quality printer. The process I have chosen to work with would seem to fly in the face of my hands-on proclivity.

This is a primary reason I currently make use of a digital process: the first image below is an oil painting I started over 30 years ago, reworked numerous times, and never finished. Re-working the gradients led to a loss of freshness and luminosity, which I desired. You can see that the multiple layers of paint have begun to slough off. I never gave up on wanting to resolve this image. There was something about the rotation of forms, the gradients, and the ambiguous relationship of foreground to background that intrigued me.

Hand painted with oils on canvas

Hand painted with oils on canvas

Digitally created

Digitally created

The second image is a recently created digital version. With the computer, I was able to try many versions of the composition, adjusting the characteristics of the gradients, the colors, and the forms in a relatively short time interval. The Elements program allowed a range of explorations that were not within my grasp with the paintbrush. After 30+/- iterations, I came to a resolution that feels right to me. I don’t think that the manual process would have ever been the way to work out the problems in this painting.

I discovered an ironic reversal of the architectural “tech geek” ethos. In architecture, technology such as CAD, BIM, and 3-D modeling are embraced and preferred as predominant tools, whereas hand-drawing and manual processes are seen as oddities/novelties (though much appreciated by contractors, I find). However, in the art world, digital art is often stigmatized as less authentic than, and inferior to “hand-made” art. As a category, it is commonly excluded from calls for work in competitions, awards, shows, etc.

Now I’m in the position of, on one hand, extolling use of the pencil for my technical drawing (no longer a conventional method), and on the other hand, extolling use of the computer for creation of my art images (also a non-conventional option). This apparent contradiction is, in fact, consistent because these choices, and all of my technology choices, are based on evaluation of how the pros and cons of each tool adds up for me. I hold that technology is best when it serves unobtrusively as a means to an end. When I find a tool that improves my process, I embrace it. When I find a need that can best be met by some new form of technology, I use it. If a tool impedes my process, I reject it. If some new gadget or program fills a need that I don’t have, I pause and reflect; adoption of such things can create a need where there was none before, and then there is no going back. So in these instances, my tendency is to resist the seduction of “the next new thing,” in order to keep life, architecture and art as simple and uncluttered as they can be.

All Images courtesy of Laura Kraft.

Feel free to share any of these copyright-protected images, but please provide a link back to 2H Pencil.

What do you think? I invite your comments.

E

E

A lost art in the world of science is the lab notebook. In it, scientists write down observations, impressions, and all the variables and outcomes of an experiment. If you are teaching STEM classes, might I suggest that you resurrect the lab notebook and have students personalize it? Give them assignments where they have to hand-draw pictures of what they see and what they predict. Let them figure out how to visually represent these things — without digital pictures, by the way.

A lost art in the world of science is the lab notebook. In it, scientists write down observations, impressions, and all the variables and outcomes of an experiment. If you are teaching STEM classes, might I suggest that you resurrect the lab notebook and have students personalize it? Give them assignments where they have to hand-draw pictures of what they see and what they predict. Let them figure out how to visually represent these things — without digital pictures, by the way.